The Real Acme

The Glorious Insanity of Turbonique

This article first appeared in Garage Magazine #14 (2007).

Most of us, at one time or another, have heard the old urban legend about a friend of an uncle of a friend of a cousin of a guy who stole a JATO rocket motor from an Air Force base, strapped it atop a Chevy Impala, and torpedoed the contraption into an Arizona cliff side at 300 mph. There’s an intense primordial appeal in that story; the idea that somebody would have the unmitigated, glorious, throbbing balls to try something so foolhardy in the pursuit of momentary thrill. The anonymous guy behind the wheel of that Impala is our modern-day Icarus, the fabled Greek of old who fashioned wings of feathers and wax only to have them melt when he flew too close to the sun. Sure, we cringe at the thought of Icarus plummeting to the sea and the Impala pilot spackled across the rock facing. But we equally envy them for their courage and ingenuity and hubris, and the rush we imagine they felt in the seconds before final climactic catastrophe.

Sadly, like the ancient fable of Icarus, the JATO story isn’t exactly true. After a thorough investigation, the mythbusting website Snopes.com concluded that the events never actually happened: “the legend of the smoldering Chevy smashed into a cliff face is pure fabrication,” it sniffs. Maybe so. But like all good yarns the JATO legend has a grain of truth, and the unvarnished truth is this: men once did strap rocket motors to their cars, and they were cheerfully supplied by the Turbonique Company of Orlando, Florida.

Though the company no longer exists, mere mention of the name “Turbonique” still inspires shudders of awe among drag racing enthusiast, the company’s principle target market. Even in the Wild West atmosphere of 1960s drag racing, its products stood alone at the zenith of no-compromise, crazyass crazy: rocket motivation for strip or street, by mail order, no questions asked. Remember Acme, that mysterious purveyor of catapults and jet skates to cartoon coyotes? Pikers, compared to Turbonique.

The architect of Turbonique’s madness was Mr. C. E. “Gene” Middlebrooks Jr. A native of Jonesboro, Georgia, Gene Middlebrooks went on to study mechanical engineering at Georgia Tech. “A damn fine ME,” recalls a former colleague who requested anonymity. “He had an innovative mind and could solve just about any mechanical problem.”

He was also in the right place at the right time. When Middlebrooks graduated college in the duck-and-cover days of the mid-‘50s, the Cold War was in full swing. He landed a job with aerospace contractor Martin-Marietta, working on the company’s propulsion system for the Pershing nuclear missile program. By 1957 the Soviets shocked the world with the launch of Sputnik, the world’s first artificial satellite, sparking the Space Race and lending even more urgency to Middlebrooks’ work at Martin.

But amid all that work to foil the Red Menace, it was clear that Middlebrooks was a gearhead. There is no record of him racing competitively, but in 1957, at the age of 25, he applied for his first U.S. patent: “Supercharger for Internal Combustion Engine.” The patent, #2,839,038, was granted the following year. Superchargers were nothing new (the first US supercharger patent was granted in 1922) but Middlebrooks’ design was based on a very novel concept. Previous pressure boost devices were all parasitic: conventional superchargers (driven by a crank pulley) and turbos (driven by exhaust pressure) both sapped power from the very same engine they were intended to pressurize. In other words, these devices take power to make power. By contrast, Middlebrooks’ 1958 patent supercharger was driven by a 12 volt DC electric motor, completely independent of the main combustion engine.

Ingenious, but the initial design proved impractical. Getting decent boost out of the electric supercharger setup required heavy batteries for power, and few were ever sold. Middlebrooks continued to tinker with self-powered supercharger designs when not working on rocket propulsion. Somewhere along the way, a light bulb went off: why not combine the two? His second patent, “Drive Control Means For a Turbo-Compressor Unit” (US #2,963,853, granted in 1960) contains a clue to his technological epiphany. The description reads:

“This invention relates to a gas-driven supercharger for an internal combustion engine… the gas which drives the turbine is supplied under this invention either by the exhaust of the internal combustion engine with which this device is used or by supplemental generating means.”

And when it came to generating supplemental gases, Middlebrooks knew there was nothing like a solid fuel rocket motor. Middlebrooks went to Miami and had Aerodex investment-cast his crazy idea in Inconel 713C alloy, and in 1962 the company – and the legend — of Turbonique was born.

He called it the AP (for “Auxiliary Power”) supercharger. Visually it appeared to be a spiral turbo with a spark plug, and was engaged with a dash-mounted switch; a sort of prehistoric Nitrous setup. When the driver threw the switch, the supercharger unit would receive liquid oxygen for ignition, and then was fed a rocket fuel named “Thermolene,” Turbonique’s trade name for N-propyl nitrate. The exhaust thrust from combustion would spin a turbine impeller up to 100,000 RPM, ramming the engine with such intense boost that it literally turned it into a giant two-stroke. Turbonique dyno-tested an AP unit on a new Chevy 409 in 1963, increasing horsepower from a stock 405 to 835 — backing up their advertised guarantee to “double your horsepower” — although it came with a recommendation not to run the unit for more than 5 minutes, and only with forged cranks, pistons and connecting rods.

Now, all of us enjoy horsepower. Still, it’s difficult, in today’s litigious safety culture, to imagine anyone sending away good money for a hop-up which involved plumbing the trunk of your car with highly volatile rocket fuel, and which could easily blow your crankshaft out the bottom of your engine. It’s even harder to believe that a company actually manufactured and advertised it.

Well mister, know this: America wasn’t always a nation of lawsuit-happy crybabies. No sir, once upon a time, before the advent of EPA and OSHA and the Consumer Products Safety Commission and rubber-coated playgrounds and multilingual warning stickers on stepladders, risk-takers walked this earth. War-hardened, devil-may-care Americans who knew that “instructions” were something to throw in the trash along with the empty Falstaff bottles. The kind of men who had a garage full of blowtorches and 110 electric welders, chain smokers who gardened with space age insecticides and tether lawn mowers, and bought their kids Jarts and clacker balls and ThingMakers and M-80s for Christmas.

It was an age when people understood that fun and risk went hand in hand, and it was in this zeitgeist that Middlebrooks found a willing customer base. One was a young Minnesotan named Ky Michaelson.

“I was drag racing a BSA bike, and I wrote to Gene when I heard about the rocket turbos and rocket motors,” he recalls. “They were very, very exciting and new at the time.”

Michaelson, who grew up in a family of daredevils and tinkerers, saw the potential in Middlebrooks’ rocket designs and became an early user and Turbonique distributor. It was Michaelson’s entrée into a 45 year career as a rocket builder and stuntman that earned him the nickname “The Rocketman.”

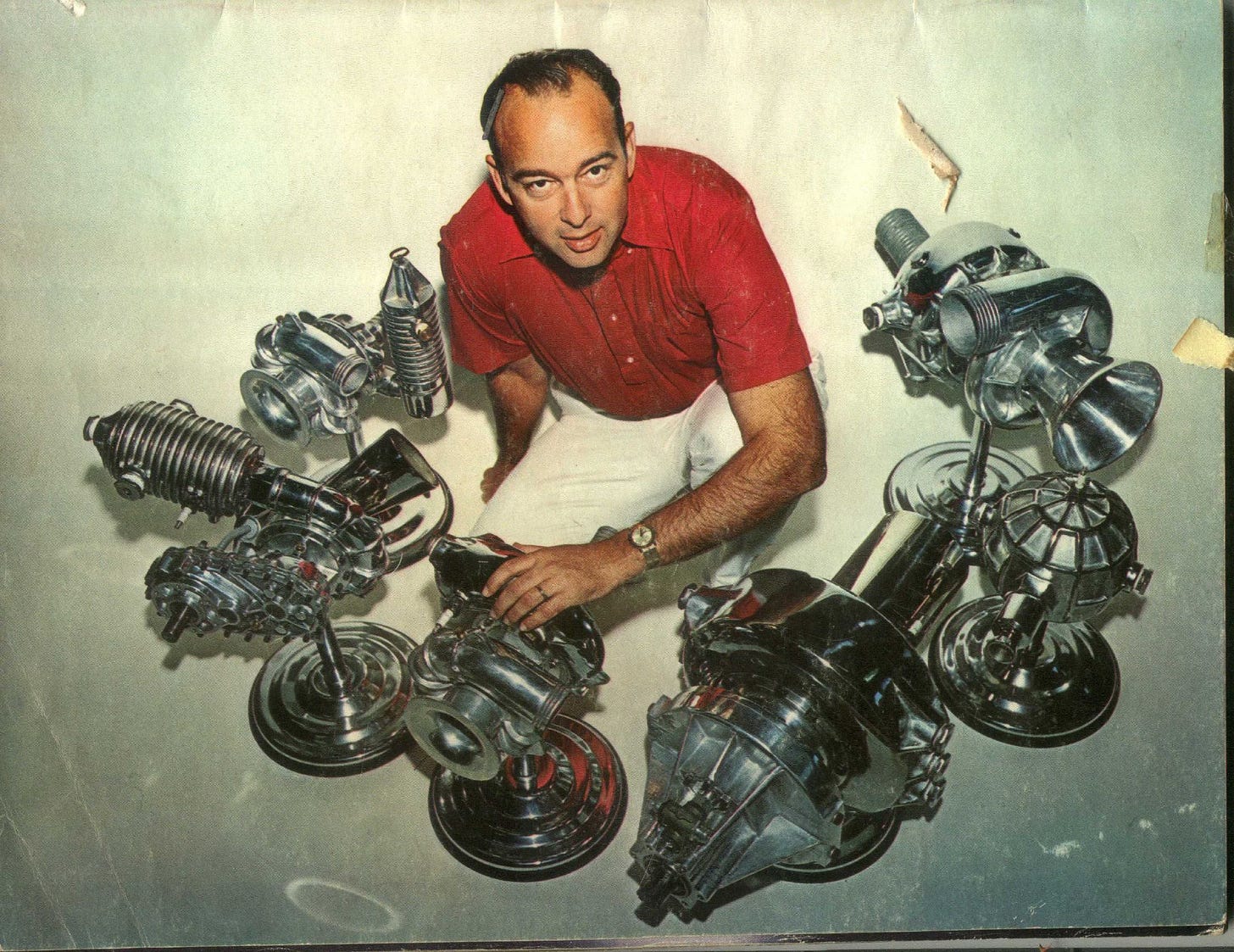

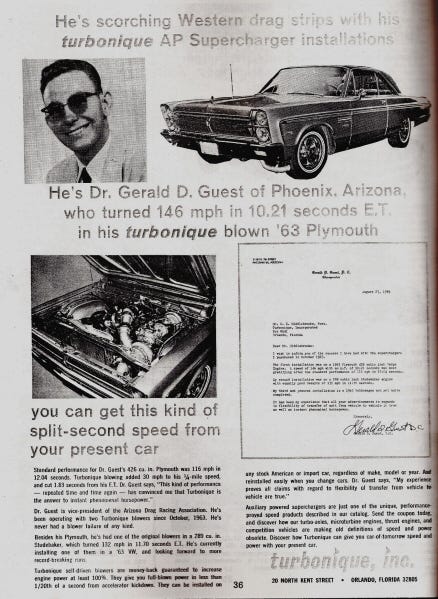

Another early customer was a mild-mannered, bespectacled Arizona chiropractor named Dr. Gerald Guest. In a 1965 letter to the company, he sang the praises of his Turbonique superchargers:

“Dear Mr. Middlebrooks:

I wish to inform you of the success I have had with the superchargers I purchased in October 1963. The first installation was on a 1963 Plymouth 426 cubic inch Wedge Engine. A speed of 146 mph with an E.T. of 10.21 seconds was most gratifying after the standard performance of 116 mph in 12.64 seconds.

My second installation was on a 289 cubic inch Studebaker engine with equally good results of 132 mph in 11.70 seconds. My third and present installation is a 1963 Volkswagon [sic] not quite yet completed. It has been my experience that all your advertisements in regard to flexibility of transfer of unit from vehicle to vehicle is true as well as instant phenomenal horsepower.”

Guest’s dragstrip feats and enthusiastic endorsement were featured in a later Turbonique magazine ad. I’m unable to determine the mysterious doctor’s current whereabouts, but as you will see, he remained a Turbonique maven for years.

The rocket superchargers sold well, but they were only the beginning (and only the mild side) of the Turbonique product line. For those interested in upgraded insanity there were Turbonique Drag Axles, which appeared to be a center section for a quick change differential, but with a mutant spaceship tumor growing from its hinder. That tumor was, in fact, a rocket engine providing direct drive to the rear axle. When not in use the car would drive under conventional power through the front drive shaft. When the driver hit the “panic button,” the rear-mounted rocket immediately engaged and began channeling One. Freaking. Thousand. Thermolene-addled rocket horsepower to the rear skins. Total weight: a scant 100 pounds. It was advised that the driver keep his thumb on the switch during operation since, having no clutch or fuel metering, the only way to control acceleration was by shutting off the fuel supply.

One enthusiastic early guinea pig for Middlebrooks’ new drag axles was Zack Reynolds of Winston-Salem, North Carolina. Reynolds had a taste for serious crazy and, as an heir to the R.J. Reynolds cigarette empire, the financial means to underwrite it. He had Middlebrooks install a drag under his 1963 Ford Galaxie, which he campaigned as the “Tobacco King.” And not just on the drag strip.

“Zack Reynolds’ Ford was street legal,” recalls Middlebrooks’ former colleague. “He kept it in his garage. I didn’t want to be near him if he was in it. Zack would cruise the streets in Winston-Salem and burp it every now and then. Gene had some misgivings about handing over such a rocket to Zack. He wasn’t sure where Zack would launch it.”

Another early adopter of the Turbonique drag axle was the barnstorming Joie Chitwood Auto Thrill Show, who installed a unit underneath the “Sizzler” ’66 Chevelle SS for traveling exhibitions. The Chevelle’s driver was a young daredevil named Jack McClure who, like Guest, would reappear in the Turbonique saga. Other famed drag axle cars followed, like the Ozark Mule Mustang and the Turbine Dart Dodge. But the most memorable installation of a Turbonique drag axle was the Black Widow VW Beetle.

The nasty little flat black Bug was Turbonique’s own, a traveling exhibition of the company’s rocket technology. It was driven by Roy “Mister Pitiful” Drew, a fearless young Black racer out of Kansas City. In a match race against Tommy Ivo’s “Showboat” at Tampa, Drew and the Black Widow shut down Ivo’s 4-engine rail with a 9.36 second pass at 168 mph, a triumph that was proudly noted in Turbonique advertising.

The Black Widow was eventually destroyed when, during an exhibition run at Tampa, it went airborne at 183 mph and tumbled through the traps. Most companies today would avoid any association of their products with a violent wreck, but not Turbonique. Its 1968 advertising prominently featured the crumpled remains of the Black Widow with Drew standing alongside, flashing a 100 watt smile.

Okay, so rocket superchargers and drag axles are all well and good, but what if you were a discerning 1960’s daredevil who really needed undiluted, industrial-grade insane? You’d be in luck, because also Turbonique provided microturbo engines. Not rocket powered superchargers, or rocket powered axles, but rocket-powered rockets: pure thrust engines, reoriented for horizontal speed.

The 1966 Turbonique catalog profiled one application: a 1964 GTO powered by twin T-22-A Thrust engines. According to the catalog caption, “the same type JATO (Jet Assisted Takeoff) kits that give aircraft short term, super performance is also applicable to automotive use.” So there you have it: the real origin of the JATO urban legend.

Other cars used the pure thrust approach, like Ed Pike’s Pegasus Cougar and Marlo Treit’s “Miss Demeanor” three-wheeled streamliner. Still, even with a rocket there’s a lot of weight and inertia involved in moving a large hunk of Detroit steel down a race track. That’s why many discerning folks opted for the ne plus ultra of Turbonique insanity: rocket go-karts.

How insane? The ’66 catalog shows official quarter mile time slips sporting E.T.s in the mid-8.8s with speeds up to 160 mph. Next to them, a small photo of our old chiropractor friend Dr. Gerald R. Guest behind the wheel of his Turbonique rocket kart, apparently to shake the boredom of too many 146 mph passes inside a Plymouth. The danger in these contraptions was sufficient enough that even Turbonique felt compelled to add a gentle warning in their sales literature:

“TOO MUCH: The above cart, which is equipped with T-21-A engines, is considered unsafe for 1/4 mile competition as pictured. The thrust/weight ratio is such that speeds over 160 mph are reached within 4 seconds.”

Turbonique, the company where safety comes first! Such pleas for moderation fell on the deaf ears of “Captain Jack” McClurg, who left the Chitwood Thrill Show to race rocket go-karts full time by the late 60’s, and eventually piloted a drag kart to over 240 mph in the early 1970s.

But hey, why stop at the drag strip? Turbonique’s literature showed all kinds of helpful rocket application suggestions — outboard boat motors, helicopters, snowmobiles, hovermobiles, and my personal favorite, a go-kart propelled by an unshielded turbine prop. On the civic side Middlebrooks developed a rocket powered water pump for firefighting. If there was an application for rocket motors, Middlebrooks seemed likely to find it.

The ultimate application? The ‘66 Turbonique catalog features this product endorsement story from an up-and-coming Montana two-wheeled daredevil:

“Motorcycle Daredevil Evel Knievel plans to soon jump the Grand Canyon with his Turbonique equipped, “Norton Atlas Scrambler.” Many of you may have heard Evel outline his plans for the Canyon jump on the Joe Pine Radio/TV show. Evel is dead serious in his plans for the Canyon jump. He is sponsored by Goodyear Rubber Company and several other large firms. Arrangements must be made for the Canyon jump with the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Navajo Chief Raymond Hokai, and the U.S. Forestry Service. Knievel plans to make the jump next summer, and has both Montana’s Senators Mike Mansfield and Lee Metcalf trying to clear the way for him. He’s also contacting Arizona’s Senators and Representatives.”

Chew on that last bit and contrast with the current state of Federal nannyism. Not only did people do crazy shit back then; actual elected United States Senators cheerfully pitched in to help them do crazy shit.

That would prove to be the ultimate high water mark for Turbonique, and soon all began to unravel. Product failures – including crashes and explosions – started occurring with troublesome regularity.

“The propylene nitrate was a problem,” says Ky Michaelson. “It had a habit of pooling inside the turbo casing when you backed off the throttle and could ignite and just grenade when you hit the throttle again. In the late 60’s Arctic Cat put a Turbonique motor on a new factory racing team snowmobile, and I warned them not to do it. It blew up and hurt the driver pretty bad, along with a couple of spectators.”

Michaelson eventually began making his own rocket motors, powered by safer and cheaper hydrogen peroxide. Turbonique stubbornly clung with propylene nitrate, possibly because the company was selling it commercially. Whatever the case, by the time Middlebrooks published the pictorial book “Hot Rotor” in 1969 the company was in deep financial trouble and under federal investigation.

It all came to an ignominious end in 1970, the details of which are dryly and dutifully recorded in the transcript of the Federal appellate case “431 F.2d 299, U.S. v. Middlebrooks, (CA5 (Fla.) 1970).” It recounts how one Clarence Eugene Middlebrooks, Jr., mechanical engineer, was found guilty on sixteen counts of Federal mail fraud relating to the sale of Turbonique speed equipment. He was sentenced to two years imprisonment and fined him $4000 on eight counts. His appeal was denied.

The government alleged Middlebrooks misled consumers into believing Turbonique products were of finished quality and ready to install, where the actual products came in a kit that needed significant machining and assembly. The truth - according to several people I spoke with for this article – is that Middlebrooks became so obsessed with designing new applications and products that he sacrificed production budget to fund expensive research and development.

“He was continually coming up with ideas and prototypes for new products,” says Michaelson. “The castings and machining were extremely expensive, and I think he tried everything to come up with the money.”

In the end, none of Middlebrooks’ new ideas ever made it into production. Today, surviving Turbonique equipment is extremely rare, in part due to its extreme heavy duty use and habit of exploding, and because some suppliers reportedly destroyed their own inventory to avoid liability judgments. Turbonique’s “Thermolene” trademark lapsed, and is now a brand of weight loss pill.

While Middlebrooks served his sentence, Evel Knievel’s fame grew. But he never got permission to do the Grand Canyon jump; eight years and a hundred broken bones after he appeared in the Turbonique catalog, Knievel made a disastrous 1974 jump attempt at the Snake River Canyon. Would he have made it on the Turbonique Norton Atlas Scrambler? We will never know. His ride that day was the “X-2 Skycycle” designed by NASA engineer Bob Truax, whom Knievel would later call “an egotistical little bastard who burned up Gus Grissom on the launch pad.” But that’s another story.

That 1974 failure at Snake River Canyon seemed to presage a new era in the American psychological zeitgeist; the rise of safety fetishism, that patronizing nerf-ication of anything sharp or dangerous or cool. Crazy guys eventually discovered an even more destructive device than rocket powered go-karts: class action attorneys. In my mind, the Canyon Jump was the single event that triggered the long cold bad trip that was the 1970s.

After completing his sentence, Gene Middlebrooks lived out a quiet life in Florida. At the time of his death in 2005, he was reportedly operating a small resort north of Orlando with his wife. There is no record that he ever designed or built another speed part, but it’s impossible to believe he wasn’t thinking about it; a man doesn’t work on rocket motors and 200 mph go-karts for 15 years and just walk away. But society and the culture had changed; risk had suddenly become bad, unwanted, an evil that government programs were aimed at eliminating. For Gene Middlebrooks – a man who spent years creating risk for willing customers – the new climate of Safety Über Alles must have been cold and inhospitable.

Will it ever get back to the way it was? I don’t know, but I’m an optimistic sort. A few months ago I stumbled upon a complete vintage Turbonique C-2-A rocket supercharger. It’s out in my shop now, where I am attempting restoration, and keeping my eye open for a worthy car project to use it on.

Anybody know where I can get a canister of N-propyl nitrate?

Holy smokes! I didn't believe anyone would have the stones to put a rocket on a kart, but apparently ol' Jack still had a pair of "unmitigated, glorious, throbbing balls" in his eighties :

https://youtu.be/Mu4elRgY-yk

Unfortunately, Dr. Guest passed away a few years ago as well. I actually heard a bit locally about it at the time because they mentioned his drag racing days. Plus, he was one of 15 or so people who actually lived in Phoenix in the 60s, so that's impressive too.

https://www.dignitymemorial.com/obituaries/phoenix-az/gerald-guest-7179979